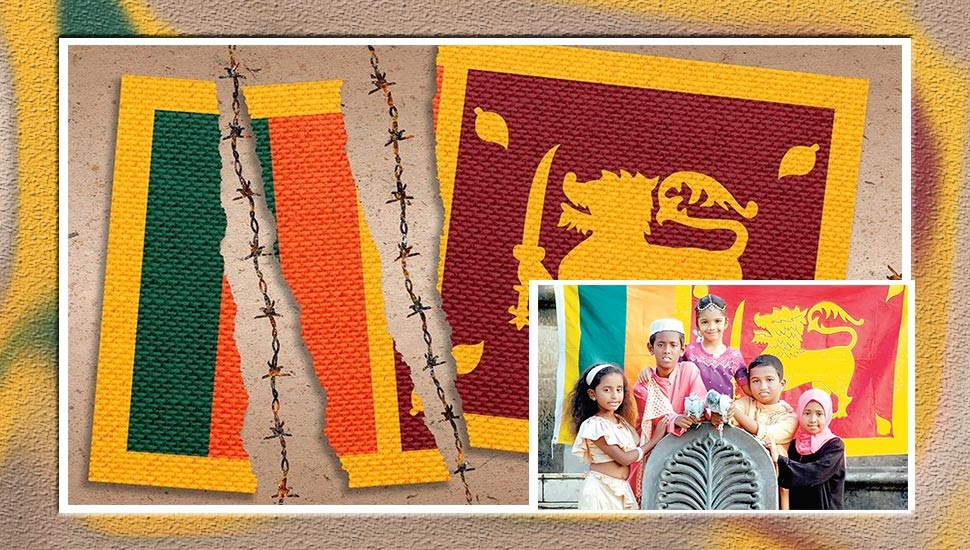

The General Election, after being delayed twice this year due to the COVID-19 outbreak, will finally be held on 5 August, and a new Parliament for the next five years will be elected. Sadly, among the common promises on political stages of a new country, there has been a notable increase in speeches and remarks driving racial discrimination.

On 28 July, the Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV) noted in a report on the General Election 2020 that many notable incidents of hate speech and divisive language were reported during the election campaign period.

The CMEV observed that the number of such incidents was lower in the beginning of the election campaign period, but increased in frequency as the campaign period came to a close.

Many candidates were seen calling to their own ethnic groups in an attempt to curry favour and gain votes, with many of their remarks bluntly discriminating against the nation’s other ethnic communities.

Several candidates were seen publiclly claiming that Tamils and Muslims are conspiring to conquer Sri Lanka, which is “the land of the Sinhalese.” There were remarks saying “Sinhala Buddhists should only vote for a Sinhala Buddhist in the election;” “Tamils and Sinhalese are suffering in the Vanni District because Muslim politicians rule the District and only favour Muslims;” “the Sinhalese will launch non-violent action against Muslims if the latter cause any more trouble to the Sinhalese;” “if Tamils are trying to separate the country and there will be rivers of blood in the North and East”.

On the other hand, a Tamil politician went so far as to boast that he was far more dangerous than COVID-19, because more than 2,500 Sinhalese soldiers were killed in Elephant Pass during his tenure as an LTTE leader in the 1990s.

Moreover, some candidates were seen going from home-to-home in areas to canvass for votes because they were ‘Sinhala Buddhists’.

Some candidates used vehicles to make public announcements in rural areas to cast votes based on ethnic grounds, while even the clergy were seen actively participating in these instances.

Racial politics as a global trend

Although racial politics are nothing new in world history, it was after US President Donald Trump’s Presidential Election win in 2016 that waves of systematic racism surged across the world. Global terrorism and a global refugee crisis were two main factors that contributed to the spread of systematic racial politics in the world, mainly in the USA and Europe.

It was reported that racial politics played a vital role in the 2016 Brexit Vote as well, while even Indian Premier Narendra Modi allegedly adopted a US presidential-style campaign in the 2019 Indian Election. His election campaign was largely endorsed by Hindu nationalists; and hate speech and racially-motivated crimes against Indian minorities, especially against Muslims, reportedly increased following Modi’s second term as Premier.

Another example for this is Brazil President Jair Bolsonaro’s election campaign in 2018. The far-right wing candidate was even charged for hate speech denigrating blacks, women, foreigners, native Brazilians and homosexuals during his election campaign.

Thoughts of the public

This writer spoke to several voters of different backgrounds and ethnicities to gauge their feelings about racially-motivated speeches on political stages in the lead-up to the election.

It was understood during these conversations that many people harbour fears about their fellow countrymen of other ethnicities. While the voters who belong to the ‘floating vote’ category lose respect for candidates who make racially-discriminative remarks on stages, the majority are actually motivated to vote for these candidates because they speak about protecting the “race and religion” that they are a part of.

The majority of voters belonging to Sinhalese community think that their “race and religion” are threatened by the behaviour of minorities. They have a huge fear of someday becoming the nation’s minority themselves. They are also burdened by the thought of minorities conspiring against them, and that they are discriminated against by minorities, in a country that rightfully belongs to them.

“After the Easter Sunday terror attack in 2019, I lost my faith in minorities in the country. We (the majority) always suffer because of the acts of minorities. We had to go through a war because of Tamils, and our people died last year because of Muslims. So I decided to vote for a person who speaks for us and our heritage,” a Sinhalese voter said.

On the other hand, minorities also fear the majority, and cast the same suspicious glances towards the majority. This fear has been exacerbated over decades due to the war, language barriers and poor communication among ethnic communities in Sri Lanka. The lack of awareness about different lifestyles, cultures and beliefs of other ethnic communities creates the perfect opening for the politicians to manipulate people into voting for them.

A Muslim voter said that he was frustrated with the racist remarks made by Sinhalese politicians. “It is like we (the Muslims) cannot even speak in this country. Whatever we do, someone finds fault in it and starts attacking us. We cannot trust Sinhalese and Tamil politicians anymore,” he stressed.

Many voters whom this writer spoke to were unaware of the election manifestos of political parties; but they had a clear recollection of the racially-motivated remarks made by certain candidates on stage. Some of them said they only came to know of certain candidates because of such remarks.

“I was not interested in X candidate until I saw a video clip created from a part of his speech on Facebook. He was speaking about how the minorities pose a threat to the existence of the majorities in many countries such as Myanmar. That speech has many things to think about. After that video, I browsed the internet and watched a few video clips like that,” another voter stated.

A large portion of the Sinhalese majority wants a dictatorship to protect them from this ‘threat of minorities’. Minorities, on the other hand, seem to want leaders that represent their ethnicities to protect them from the majority Sinhalese. The fear factor plays a key role in both instances.

Politicians exploit the situation and take calculated risks to bank on specific ethnic communities as voter-bases, despite the fact that such tactics risk the loss of floating votes.

“Conducting racially-motivated election propaganda has become more systematic and well-planned in the present,” said Aminda Lakmal, Senior Lecturer at the Department of Marketing Management of University of Sri Jayewardenepura.

“Racism is an emotional attribute. It is not a secret that in Sri Lanka, racism is mainly displayed during election times. There is a concept in Marketing Management named Point of Difference (POD). In marketing management, to gain the expected result, the brand should differentiate itself from other similar brands; that is called POD. Many political parties use the nationalistic sentiment in people’s minds as their PODs during election campaigns,” he said.

Election candidates use different approaches for highlighting their PODs, such as speeches on stage, word-of-mouth, viral campaigns, advertisements, etc.

“The content delivered at the political stages continuously highlights ‘nationalism.’ But the problem arises when the content goes through the communication process according to the decoding level of the listener, where it is stored as ‘racism’. The best example for this is the recent video that went viral on social media, which showed a candidate walking from door to door asking votes only from Sinhala Buddhists, saying he did not need votes from other ethnicities.”

Violation of Media ethics

The Code of Ethics of the Editors’ Guild of Sri Lanka adopted by the Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka says, “A journalist shall not knowingly or wilfully promote communal or religious discord or violence.

“The press must avoid prejudicial or pejorative reference to a person’s race, color, religion, sex or to any physical or mental illness or disability. It must avoid publishing details of a person’s race, caste, religion, sexual orientation, physical or mental illness or disability unless these are directly relevant to the story.”

However, in the present context it can be seen that the majority of journalists and editors do not adhere to this Code of Ethics. Unfortunately the media, knowingly or unknowingly, contributes to the spread of racism during election seasons. Most of the time, opinions of the upper management of media stations overpower the work of journalists and editors.

Speaking on the matter, a former journalist said that the way of reporting certain news items during election times was completely based on the views of the upper management of the TV station he worked at.

“As a result of that, sometimes it does not matter if journalists try to stay neural and within their ethical grounds. They have to follow the instructions from above,” he noted.

Furthermore, Tharindu Jayawardena, a journalist and Former Secretary of Sri Lanka Young Journalist’s Association (YJA) said, “The Election Commission (EC) has a Gazetted Code of Ethics to be followed by the media during election times. That Code of Ethics clearly states that the media should not report news in a way that could flame racism.

The Code of Ethics of the Editors’ Guild of Sri Lanka adopted by the Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka also states that the media should never promote racist propaganda, not only during election times. However, we do not see many media stations and journalist adhering to this ethical framework. There are several reasons for that.”

Jayawardena noted that many journalists do not want to produce and write racially-motivated news stories.

“But they are left helpless when they get instructions from the upper management of their institutions. Many of them produce such news stories just to protect their jobs. For an example, one journalist told me he was instructed to edit a news story relating to Doctor Shafi Shihabdeen’s alleged sterilisation surgeries on women in a racially discriminative manner. He was really frustrated after that.”

Jayawardena alleged that a few mainstream media stations have actively contributed to spread racially motivated propaganda campaigns throughout the country. As a result of this, people tend to criticise other journalists who try to provide correct facts and details against those racially motivated propaganda campaigns.

“The General Election 2020 is mainly based on racism. This became more severe after the Easter Sunday terror attack in 2019. Many Sinhalese politicians openly carry promote racist agendas for votes from the Sinhalese community. Tamil and Muslim politicians do the same.

“In such a backdrop, it is hard for journalists to maintain ethical grounds. Apart from that, many Sri Lankan journalists are not aware of election Laws and regulations, election reporting and media ethics,” he pointed out.

The Election Commission has also issued a Code of Ethics to candidates and political parties to discourage them from relying on hate speech, racism and sexism on stage. The EC’s Code of Ethics for journalists and media stations during the election times clearly states that the media should not give any publicity to such stories.

However, the EC does not have a power to take actions against the candidates and media which promotes hate speech and racism due to the lack of legal provisions, stated Assistant Election Commissioner, Suranga Ranasinghe.

He noted, “We can only instruct candidates and the Media to not promote hate speech and racism during the elections. Apart from that, no action can be taken against those who violate the Code of Ethics we issued due to the lack of legal provisions at the moment. But we have a partnership with Facebook on hate speech on the platform, and because of that, we can request Facebook to remove such stories.”