Pre-internet law hamstrings polls chief, watchdogs

Offensive posts and memes ridiculing or dehumanising political leaders and the Election Commission chief that went viral on Facebook during the run-up to the August 5 parliamentary polls still linger despite multiple reports by watchdogs.

Such memes, often likening their targets to animals, appear to clearly violate Facebook’s own Community Standards but the social media platform does not think so. Facebook has 6.2 million active users in the country.

One degrading meme showing the Chair of the Election Commission juxtaposed with a snake made of money was not taken down even after repeated reporting by a local youth-run social media monitoring group. A similar meme involving the Prime Minister was removed immediately.

The Election Commission was toothless when it came to removing illegal election-related content on social media platforms.

The commission began a pilot project working with Facebook Inc. through a dedicated channel but the project was ill-equipped and lacked personnel to actively monitor platforms. Currently, the commission depends on election watchdogs to initiate investigations and pass on reports that it, in turn, passes on to Facebook and other social media platforms.

It acknowledged that it could not immediately remove illegal propaganda from Facebook, taking from three to more than 12 hours to remove some links through its dedicated channel.

Assistant Election Commissioner Suranga Ranasinghe, who heads the body’s Election Dispute Resolution Unit, told The Sunday Times since the commission does not engage in active monitoring, it can only forward reported links to Facebook, with which it has “a mutual understanding”, when complaints from watchdogs are received.

“Since this is a pilot model of collaboration with the commission and social media platforms, we are satisfied with the steps taken by them during the parliamentary polls compared to last year’s presidential election,” Mr. Ranasinghe said while stressing the new parliament must change the law to give teeth to the commission to regulate digital space.

With little investigative and no punitive functions, and no official Memorandum of Understanding, the commission merely functions as a trusted partner between watchdogs, civil society organisations and social media platforms.

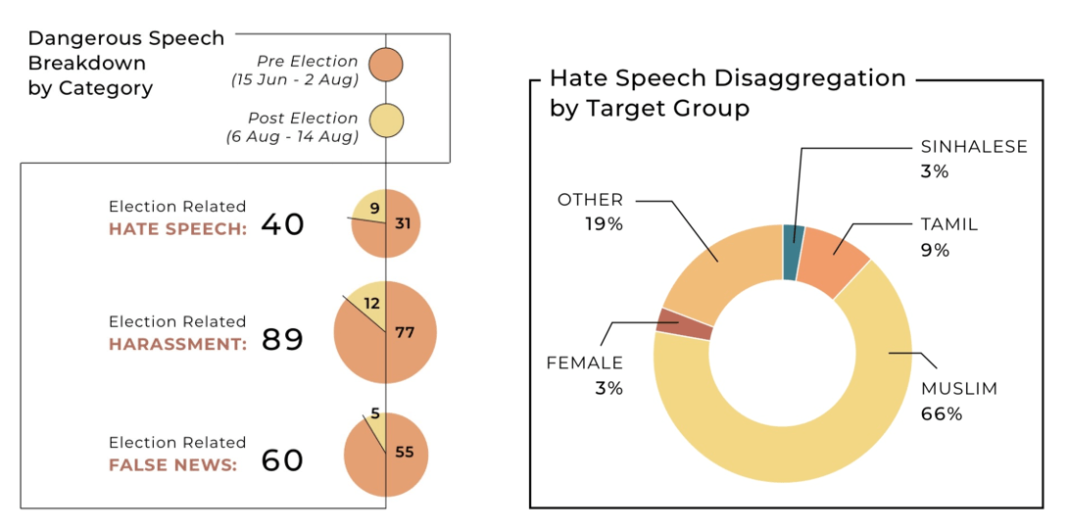

According to Hashtag Generation, a youth-led initiative that monitored social media through the election period, only half the 40 incidents of hate speech-related incidents reported to Facebook through the Election Commission were taken down. The rest were not considered to have violated the platform’s Community Standards.

On Youtube, popular among youth for its vlogs and entertainment content, Hashtag Generation reported six problematic videos of which only one was restricted and no action taken on the rest.

Hashtag Generation partnered with the Peoples’ Action for Free and Fair Elections (PAFFREL) on the monitoring exercise.

In its final report on the August polls, Hashtag Generation noted that “relatively peaceful and calm campaign on the ground contrasted with the divisive rhetoric online, some of which amounted to hate speech”.

Most of the hate speech content on Facebook, according to Hashtag Generation, was targeted at the Muslim community, including Muslim politicians. “Islamo-racist hate speech accounted for approximately 65.6 percentage of all hate speech incidents recorded,” the youth group said.

The National People’s Power (NPP) coalition was the biggest victim of false news propaganda by coordinated groups, targeted by 72 per cent of the incidents recorded by Hashtag Generation.

The main problem preventing the Election Commission and election monitoring bodies from taking legal action against online violators is the inadequacy of the law. Parliamentary elections are held under Parliament Elections Act (No. 1 of 1981), which was adopted long before the birth of the internet.

“There is no clarity over how election laws are being applied to the internet. It makes things difficult for us monitors as there is no clear interpretation of the law and regulations. It is a big gap,” Hashtag Generation Director Senel Wanniarachchi said.

Prihesh Ratnayake, a social media analyst with Hashtag Generation, said the group had monitored at least 450-500 sites, including gossip pages, that ran content varying from sensitive ethnic issues to humorous memes.

Facebook, the best-known social media platform in the country, failed to ensure political advertisements were not allowed during the “cooling period” starting two days before election day on August 5.

During those days, millions of Sri Lankan Facebook users were subjected to well-targeted political campaigns depending on their geographic location. Users found thousands of paid political ads featuring on their Timeline.

According to Hashtag Generation, more than 5,000 political advertisements ran on Facebook during the cooling-off period despite a warning issued by the Election Commission.

Of these, 3,570 ads were reported to Facebook and 3,553 of them were removed but only after several hours: it took more than 12 hours to remove 742 links from the platform while another 811 links were removed only after nine hours had elapsed.

“We shouldn’t be identifying each of those paid ads and reporting back to the commission for removal. Facebook’s advertising facility should have been disabled for political ads during the cooling-off period to prevent the ads appearing on those platforms in the first place,” Mr. Wanniarachchi said.

He said that while monitoring took in the official sites of parties, which spent millions of rupees on political ads, there were other influential sites that could not be monitored at all.

One advance from the presidential elections last year was that Facebook enabled its Ad-Library facility for the parliamentary polls for transparency purposes, allowing parties’ campaign expenditure details to be viewed.

This action helped in monitoring parties’ official, verified sites but left invisible the spending by groups or individuals running thousands of political sites.

| Ads allowed to live if they pass FB’s sniff test | |

| Facebook Inc reiterated that if the platform did not take content down, it was because “it likely did not violate its Community Standards or it did not violate election law”.Responding to a questionnaire sent by The Sunday Times, it said its Community Operations team is global and reviews reports around the clock in several languages, including Sinhala and Tamil, and that most reports are reviewed within 24 hours. It stressed that it does not remove content just because it has been reported a certain number of times and that even one report could trigger a review. Content is removed only if it violates Facebook’s standards. In order to ensure safe digital space by restricting the spread of viral misinformation and harmful content being shared, Facebook also introduced a forwarding limit on Messenger in Sri Lanka and several other countries, where messages can only be forwarded to five people or groups at a time. |

| Just mudslinging but it’s a real concern: Rambukwella | |

| Seasoned media-savvy politician Keheliya Rambukwella, who held the post of Ministry of Mass Media until 2015 and was reappointed to the same ministry after the August polls, says the role of social media in shaping public opinion on politics, particularly during elections, is a real concern.Nevertheless, he said, the public knows platforms have become tools for mudslinging campaigns. In the worst cases, he said, platforms could be liable for defamation.“Even when I share some stories I picked up on those media platforms with my children, they are sceptical about the accuracy and make fun of its origins. That’s how the credibility of those platforms has gone,” Minister Rambukwella said.As an example, Mr. Rambukwella pointed to a photograph of Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa greeting the late film director Lester James Peries, where Mr. Peries’ face was photoshopped with that of Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) arms procurer Kumaran Pathmanathan to launch a mudslinging campaign last August.Minister Rambukwella is of the view that Singapore’s fake news law, the Protection of Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill (POFMA) is “draconian” and has ruled out similar action by this government to regulate social media and news websites.Instead, he said, his ministry is studying Indian attempts to formulate a participatory mechanism to ensure platforms are not being used for mudslinging and misinformation campaigns. |

[This story is part of an election reporting series supported by CIR. It was originally published in Sunday Times on 13 December 2020. Link: http://www.sundaytimes.lk/]