By Aanya Wipulasena

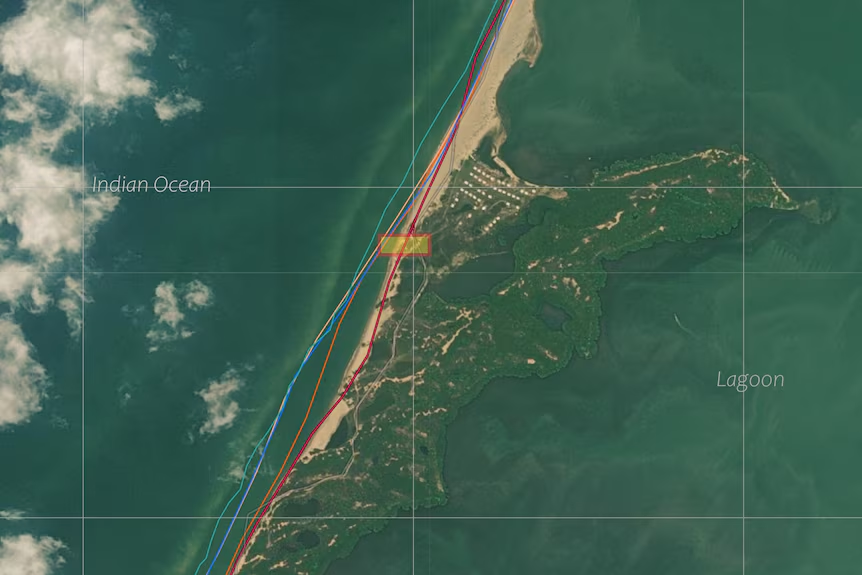

Vinisious Obrey Fernando, 42, points at a map of Keerimundalam, a village located on Kalpitiya peninsula in north-western Sri Lanka.

“This is where my father’s house used to be,” he said.

“Now our house and most of that land has gone to the sea.”

His face wore a sad smile.

About 20 years ago, Mr Fernando’s village was a tranquil coastal haven with a thriving community of nearly 300 families living in cadjan houses.

It had a school, a post office, and a church more than 210 years old. Now, with the land swallowed by the encroaching sea, Mr Fernando could only reminisce about what once was his family home and vibrant neighbourhood.

In 2014, he and his family relocated to Kalpitiya town area, with a population of around 96,000, like most of his neighbours as their village became uninhabitable.

The map depicting the grave reality of the situation shows over 90 per cent of his land has been lost to sea erosion. He only managed to salvage parts of the roof and doors of the house as the water rose.

By mid-2024, Mr Fernando could still see the last remaining wall jutting out of the water.

By the time of the publication of this article, Mr Fernando’s father’s house was completely washed away.

During the low tide, he can stand where his father’s house once was.

“That was the house my two siblings and I grew up in. I used to play volleyball and elle, a popular bat and ball game in Sri Lanka, with my brother on the land in front,” he said.

“We used to catch fish in the sea. My father was the village sub-postmaster, and I even met my wife there.”

On the weekends, the coastal village (Keerimundalam) is eerily deserted.

“This village used to be filled with chatter and laughter. Our friends and relatives have all left now. I feel very lonely sometimes”, said local resident Mekala Santhanal Peiris.

“Will the rest of the village also go into the sea? This is all I think about. I am scared we will lose everything we have.”

Ms Peiris moved to Keerimundalam about 20 years ago after her marriage. When the water kept rising, she said, the villagers did everything they could to save it.

With the help of the church and villagers, they built a monument for Sinthathiri Maatha (Lady of Good Voyage), whom the villagers believed would save the village from the sea.

However, now, the sea engulfs the monument’s base when the tide is high.

As the sea continued to claim the land, Mr Fernando and other villagers tried to stop by stacking sandbags, to no avail.

The president of the Uchchamunai, Velankanni Matha Rural Fisheries Organisation, Sebastian Dias, said the sandbags were placed two years ago.

“That plan was a failure. Now even the sandbags are in the sea,” he said.

For villagers like Ms Peiris, Mr Fernando and Mr Dias, this is not just about the loss of property; it’s the erosion of a way of life which was deeply rooted in the rhythms of sea, community, and spirituality.

The profound loss of their homes and lifestyle carries a heavy weight. Most of their neighbours and loved ones have relocated to Kalpitiya town.

“During the church feast, the whole village celebrated, and when there was a funeral, the whole village mourned. That has all changed now. Now we don’t even know who died,” Mr Dias said.

“The sea took away our identity from us”.

Father Sampath, who has been serving in the Kalpitiya Peninsula for 15 years, said the village church, Holy Cross Church, was important to Keerimundalam and surrounding villages.

With its long-standing history and spiritual presence, the Holy Cross Church brings villagers together.

“During the church feast, which we have in the second week of September every year, almost 3,000 people come to the celebrations. It is a big function,” Father Sampath said.

“Now the sea is near the church. So many houses in front of it are gone to the sea.”

A recent comparison by Geographic Information System (GIS) experts between a survey plan made in January 2005 and a high-resolution satellite photo reveals there is nearly no land left.

A 2023 study highlighted that wave climate data from the area shows significant morphological changes, meaning that there are alterations observed in the shape, structure, and features of the coastal line, while intensified wave climate, especially during the south-west monsoon, leads to slow erosion of the Kalpitiya peninsula.

Another study, also in 2023, found that the island’s western coast shows high vulnerability as a result of fewer coastal barrier ecosystems, meaning that most barrier-effective coastal ecosystems in the area have already been degraded and removed.

Seinulabdeen Haleema, 59, strolls along the sand with her two grandchildren. A light rain forces the children to find refuge as Ms Haleema takes out her umbrella.

Closer to the seawater, to her right, a once-thriving plantation of mangroves withers, and to her left, further inland, barren stumps of coconut trees punctuate the landscape. She remembers well what the coastline looked like in Kalpitiya decades ago.

“Can you imagine, we used to play on the sand there?” she said, looking into the sea.

Her father bought land in Muhuttuwaram, Dutch Bay, about 40 years ago. They had a mud-thatched house, now claimed by the sea, where her grandparents used to live.

“We were seven siblings in the family. We came to this land on my father’s bullock cart. It was a joyous time,” she recalled.

The land she stood on now, she said, is unrecognisable. It was abandoned. Ms Haleema rarely makes the journey to visit it.

D.T. Rupasinghe, chief engineer at the Coast Conservation Department, has been studying erosion in the Kalpitiya peninsula.

“This is Sri Lanka’s most sensitive area due to its geomorphology. It is very dynamic with big variations”, he said, adding that years of research have shown that the islands in Kalpitiya are eroding and shifting landward.

Mr Rupasinghe said that changes in wind patterns, wave patterns, and changes in current were causing the shift.

“We know that these changes are driven by climate change, but we need a database and run numerical models to make that connection. We don’t have the resources to do that,” he said.

He pointed out that human activities and natural changes in the environment also contributed to aggravating sea erosion in Kalpitiya.

The Coast Conservation Department is planning to use geo-bags to stop sea erosion in the Kalpitiya Peninsula following the villagers’ request. However, officials are concerned that it would worsen the situation rather than help.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its sixth assessment report, projects a likely global mean sea level rise of up to 1 metre by 2100, relative to the beginning of this century, under a very high emissions scenario.

The report also presents a low likelihood, high-impact storyline where the global mean sea level rise (relative to 1995-2014) could be up to 1.6m by 2100, further increasing up to 4.8m by 2150.

Roshanka Ranasinghe, Professor of Climate Change Impacts and Coastal Risk and member of the expert scoping team for IPCC, said it was essential that detailed studies were done in coastal hotspots to see what adaptation measures were necessary.

“I recommend authorities look at the results of global trends and identify areas that are vulnerable and have a big impact on the economy,” he said.

State authorities are both aware and concerned about the situation. The director of the country’s Climate Change Secretariat, Leel Randeni, agreed there was a need for real-time data.

“There is some research on sea erosion, [but] there are many gaps that need to be revisited”, he said, adding that though Sri Lanka is not a major carbon emitter, it was among the most affected countries by climate change.

Meanwhile, Mr Dias is leading the call to protect the area. His organisation has also written the state officials regarding the villagers’ plight.

A letter dated October 6, 2024 and addressed to President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, calls for urgent intervention to protect the coast.

“In Keerimundalam village, there is a 211-year-old church, 50 houses built by the state, a sub-post office, and an electricity transformer. While villagers have worked hard to protect these, their fishing activities have been affected,” the letter points out.

In reply, senior assistant secretary to the president W.M. Bathiya Wijayaratne wrote an official letter asking the District Secretary to present the villagers’ appeal to the next coordination committee and provide a “quick” solution.

Mr Dias said there had been no reply to this letter. He said he was observing the sea claiming the village, and with it, his people’s lifestyle, identity, and culture.

The villagers are keen to have discussions with relevant authorities. They worry that their calls are not heard.

When discussions around climate change often take the form of economic impacts, it is crucial for authorities to listen to the profound human stories behind the numbers and to address their concerns, Mr Dias and Mr Fernando said.

When he finds time, Mr Fernando still goes to where his family’s house once was in Keerimundalam. Following in his father’s footsteps, he is the area postman. The post office has now shifted to the abandoned school building after the original building was damaged by the sea.

Often, he wishes he could return to his village. Many houses are submerged, out of sight.

Now, the sea levels have reached the churchyard.

“If the church goes to the sea, there will no more be a village there, and that is my biggest worry.”

This story was produced under the CIR- CANSA Media Fellowship Programme. It was originally published in ABC on 06 March 2025.