By Kamanthi Wickramasinghe

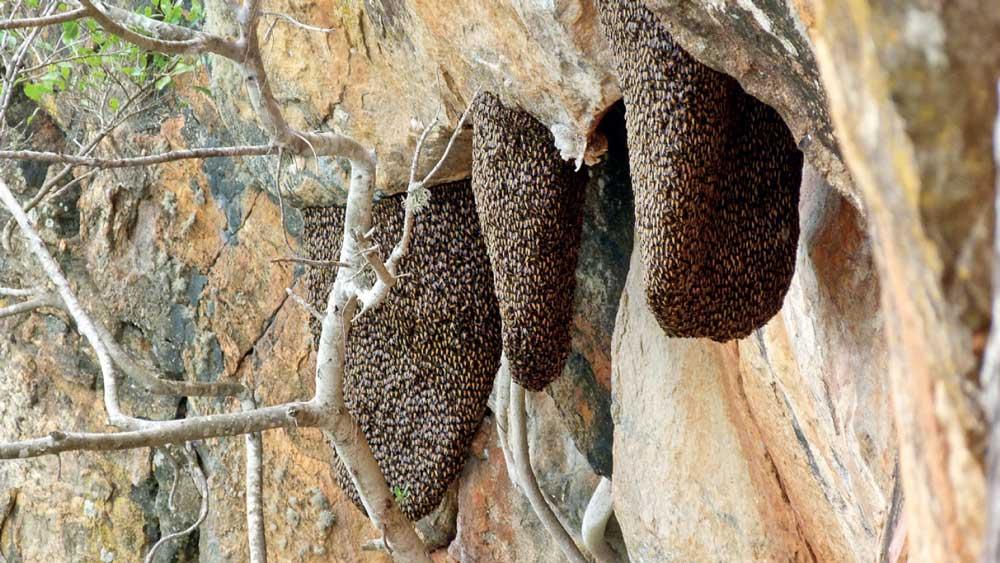

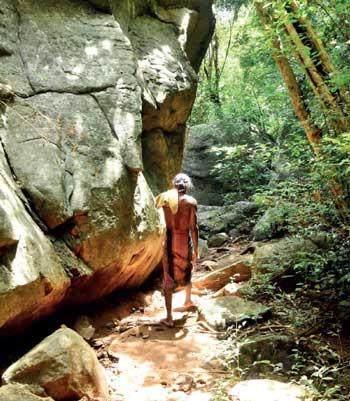

For Danigala Mahabandalage Suda Wannila Aththo, the incumbent leader of the Rathugala adivasi community, bee-honey harvesting is part of their traditional lifestyle. Rathugala is a scenic village in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka, located bordering the Gal Oya region in Ampara District. Following a prayer dedicated to Kalu Bandara deiyo, a local deity whom they believe is a guardian of the thick jungles they live in, Suda Wannila Aththo and his group would carefully advance into the jungles, in search of bee hives, usually located atop steep cliffs. Unlike in the past, the chances of returning with a bounty of bee honey is rare as this forest-dwelling tribe faces multiple challenges to collect bee honey. Amongst them are a long list of government regulations that prohibit them from entering jungles and a decline in honeycombs due to loss of pollinator habitats largely due to climate change impact.

centre underscores the risks associated with

wild bee honey harvesting

Image Credits – Kithsiri De Mel/ Daily Mirror

A fading tradition

Traditional bee honey harvesting is a risky occupation. According to Charles Gabriel Seligmann’s book titled ‘The Veddas’, published in 1911, bee honey harvesting was once referred to as a ‘game’ where young boys in a tribe are taught to extract honeycombs without getting stung. They would initially set fire to some leaves beneath them as they believe that the smoke would chase away the honeybees (Apis cerana). The boys would then suspend themselves with a ladder made of creepers to slowly carve out the honeycomb off the rock using a tool known as the masliya, a stout stick about two and a half metres long with four prongs at one end, which the adivasi carries hanging by a loop from his forearm and which he uses to detach the comb and convey it into the maludema, the vessel that is used for collecting honeycombs. The thrill of bee honey collecting on an onlooker hasn’t changed (much) from how Seligmann, a lecturer in ethnology at the University of London described it from a first-hand experience. But today, this traditional practice is coupled with multiple challenges that have restricted the Rathugala adivasi community to a limited area within their home ground.

One of the earliest references to the adivasi community (previously known as Veddas) was by Robert Knox. In his accounts in 1681 believed to be the first accurate description of the Veddas, Knox describes a peculiar way in which they store venison. “They cut a hollow in a tree, put honey, fill it with flesh and stop it with clay,” it reads.

The Rathugala adivasi community is considered among the last remaining forest-dwelling people of Sri Lanka, carrying with them a rich cultural heritage. According to a 2023 research by the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), the adivasi community lost some of their best hunting grounds and caves which were inundated by the Senanayaka Samudraya built as part of the Gal Oya Irrigation Scheme between 1949 and 1952. Since then, their traditional lands were destroyed and some of these lands were declared as catchment areas of the reservoirs, banning their hunter-gatherer practices.

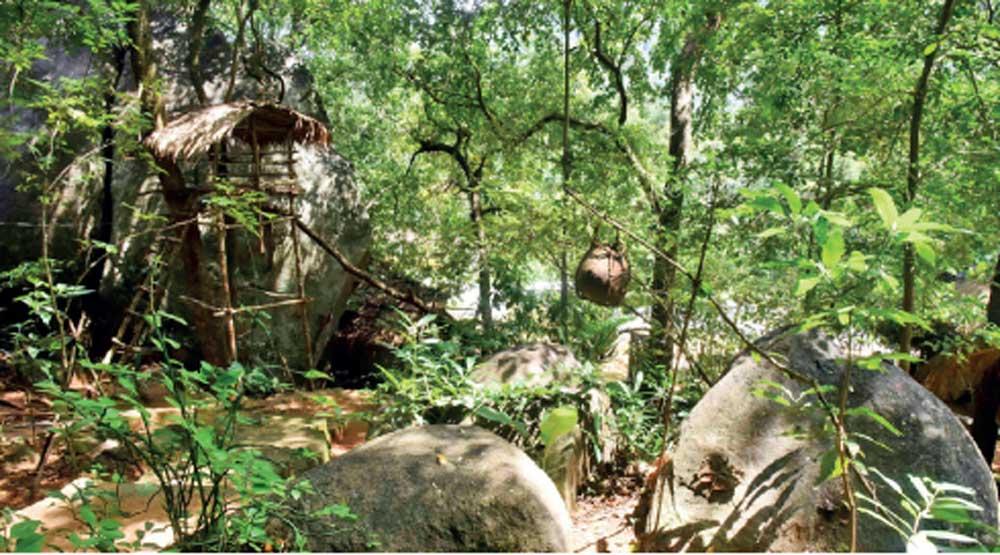

“Back in the day we used to walk freely in these jungles and collect bee honey for our daily requirements,” Suda Wannila Aeththo told the Daily Mirror during our visit to the Rathugala Vedda Heritage Centre situated along B562 (Bibile-Ampara road). “Today, we observe serious changes in these environments. The jungles of yesteryear were so rich in diversity. There were various native plants which we used for medicine and food. We didn’t have to worry about food, and it wasn’t costly like today,” said Suda Wannila Aeththo.

Bee honey harvesting was more of a cultural practice, he said. “If a girl is of marriageable age, the potential partner would carry honey, dried venison and other cultural gifts to express his interest in marrying her. But today, it has become difficult to collect bee honey. One reason is the existing government regulations: many of these jungles are now designated as forest reserves. Another reason: there are less suitable trees for pollinator insects like bees to thrive on. We find more invasive plant species such as lantana spreading rapidly, dominating the space required for native species. Many native plant species such as Bin Kohomba (Munronia pinnata) have become so rare that we doubt whether such plant species have already become extinct,” he added. According to the 2020 National Red List Bin Kohomba falls under the Endangered list of medicinal plants.

Rapid forest degradation

Pollinator insects such as bees and butterflies play a crucial role in ensuring food security, globally. Sri Lanka is home to nearly 150 species of bees—and four of them produce their own honey. Amongst them, the Asian honeybee (Apis cerana) is the most common species. However, bee researchers observe changes in bee populations due to rapidly diminishing forest cover.

“With rapid human population and the progressive denudation of forests in the past few centuries, bee honey production from natural forest reserves has been rapidly declining,” writes Dr. S. P. R Weerasinghe, Director of Agriculture in Dr. R. W. K Punchihewa’s book ‘Beekeeping for Honey Production’ published in 1994.

Sri Lanka is a signatory to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), ratified in November 1993 and was put into effect in March 1994. The 2017 Forest Level submission indicates that Sri Lanka has a forest cover of 29.1% thereby making a commitment to increase it to 32% by 2030 including forests as well as plantations.

People who engage in domestic bee honey production have started selling bee honey at nominal rates. So, we can’t charge a premium price. It’s a premium product because we provide authentic bee honey. Many of us are indebted. Some of us have even obtained bank loans. Back in the day we weren’t indebted to anyone when collecting bee honey. But things have changed

– Suda Wannila Aththo, Leader of Rathugala Adivasi Community

There are around 20,000 species of bees around the world and Sri Lanka has around 150 species. We are particularly interested in the Asian honeybee (Apis cerana)

– Dr. Anura Indrajith, Entomologist at Rajarata University

It is important to protect honeybees and wild bees because they are key pollinators in any ecosystem. Providing legal protection for honeybees will also put a halt on wild harvesting of bee honey which has a negative impact on their survival

– Dr. Jagath Gunawardena, Senior Environmental Lawyer

Bee honey is used as a supportive material when preparing Ayurveda pharmaceuticals. It is used as a natural sweetener and a preservative as well. But there are two types of bee honey, the new and old and each one of these types has their own medicinal properties

– Dr. Nirasha Gunaratne,

Head, Department of Dravyaguna Vignana at Gampaha Wickramarachchi University of Indigenous Medicine

A 2001 study on forest policy trends in Sri Lanka indicates that the island’s natural forest cover decreased from 85-70 percent during 1881 to 1900, a time period which belonged to British rule of Ceylon. The central hills were cleared for export crop plantations, while the dry zone forests were logged for valuable timber. After the country gained independence in 1948, 2.9 million hectares (44 percent of the total land area) were still under forest cover (Dissanayake et al., 1983). By 1981 forest cover had been reduced to 1.63 million hectares (85 percent of total land area), representing a decrease at the rate of 50,000 hectares per year (Bandarathilleke, 1991).

Pollination crisis

A 2023 study on forest cover and natural vegetation loss shows that in 2000, 61.38 percent of the country had above 25% canopy density. But by 2020, the forest cover of these areas decreased by 52.78 percent. Data gathered during this study shows that the forest cover density in Anuradhapura, Kurunegala and Monaragala districts remain at 12.06%, 9.82% and 8.49% respectively.

A decline in forest cover also means a decline in potential pollinator habitats. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its special report on Global Warming shows that climate change directly contributes to the loss of insects’ habitats.

According to Dr. Anura Indrajith, Entomologist at Rajarata University, one of the persisting issues is the lack of data on the number of natural honeybee colonies in the country. “There are around 20,000 species of bees around the world and Sri Lanka has around 150 species. We are particularly interested in the Asian honeybee (Apis cerana). Ten years ago, if we wanted to find a honeybee colony, we would go to a forest area. But nowadays it’s very difficult to find natural honeybee colonies. The European honeybee (Apis mellifera) can be found in the West,” said Dr. Indrajith.

Dr. Indrajith also noted a declining trend of giant honeybee (Apis dorsata) populations. However, bee researchers are challenged with lack of data to give an accurate estimation of the decline. He said that in Germany for instance, honeybee colonies have declined by 57% over the last 15 years. In UK it is 61% and India has experienced a 30% decline in past 25 years.

Climate change impacts on Asian honeybee

So far the Asian honeybee has been managed in its native ranges within South and East Asia. The reasons for the decline in natural honeybee colonies are manifold. “Bees and plants have a close relationship. If the flowers are not available due to heavy rain or drought there will be a scarcity of food for the honeybees and the population will experience a decline. During the drought (around August), there aren’t many flowers even on ornamental plants. Bees also need water. If there’s no water source around, they experience a lot of stress. On the other hand, during deforestation, they may not find enough nesting sites. As a result, they will go deeper into the jungles or away from the area,” Dr. Indrajith explained.

Honeybees are also prone to pests and diseases in the face of climate change. Studies indicate that warmer falls allow the varroa mites season to last longer. “In addition, honeybees are also threatened by wax moths that increase with changing climatic conditions. Even though the Asian honeybee is resistant to most pests and diseases, it’s smaller in size when compared to the European honeybee and is less adaptable to climate change,” Dr. Indrajith added.

As told by Suda Wannila Aththo earlier, climate change is one factor that fosters the growth of invasive species such as lantana, Guinea grass (Megathyrsus maximus) which further compromise pollination patterns of pollinator insects. When invasive plants overrun native plants and establish a monoculture, the area may be more susceptible to wildfires or pests. This phenomenon may intensify the effects of climate change on humans and the environment.

A 2023 study on beekeeping under climate change indicates that the brood-free period for colonies will likely be shorter or even completely absent due to raising temperatures. This will cause a negative feedback loop, which will increase the impact of pests depending on the brood for their reproduction.

Demand for pure bee honey

Pure bee honey also includes various health benefits in traditional schools of Sinhala medicine including Hela Vedakama and Deshiya Chikitsa in addition to Ayurveda and Unani schools of medicine. “According to Ayurveda textbooks, there are various types of bee honey depending on the color, the type of bee that produces the honey and various other factors,” said Dr. Nirasha Gunaratne, Senior lecturer in Ayurveda Pharmaceutics and Head, Department of Dravyaguna Vignana at Gampaha Wickramarachchi University of Indigenous Medicine. “According to Charaka Samhita, a Sanskrit text in Ayurveda medicine there are four types of bee honey whereas the Sushruta Samhita mentions eight varieties. Bee honey is used as a supportive material when preparing Ayurveda pharmaceuticals. It is used as a natural sweetener and a preservative as well. But there are two types of bee honey, the new and old and each one of these types has their own medicinal properties,” explained Dr. Gunaratane.

Dr. Gunaratne explained that ‘new bee honey’ includes Vrumhana Guna (properties that nourish the body), properties to increase energy and strength while enhancing nutritional support for three bio energies in the body (Vatha, Pitha, and Kapha) in addition to laxative effects. “Old bee honey on the other hand supports anti-diarrheal actions, controls obesity and has more medicinal properties than new bee honey,” she explained while adding that it also includes anti-diabetic properties.

But she warned that pure bee honey is slowly becoming a rarity in the market. With adulterated bee honey, it has become a challenge to obtain pure bee honey that’s prescribed for patients. But there are several parameters to check if a bee honey sample has been adulterated. “There are simple tests such as adding a teaspoon of bee honey into a cup of water. If the honey settles at the bottom, it is pure. Adulterated bee honey would mix with water without a trace. Then there’s a flame test. You can simply soak a wick in bee honey and burn it. If its pure bee honey, the flame would spread. Adulterated bee honey has a certain percentage of moisture, and the flame would go out. A blot test is where you add a drop of bee honey on a tissue paper and firmly squeeze it. There would be some moisture if the sample has been adulterated. Another way to check for adulterated bee honey is to add a drop of bee honey onto your thumb. If it moves, then the sample is adulterated,” Dr. Gunaratne said, adding that patients should always look for pure bee honey in the market.

Sustainable beekeeping – The way forward?

Bee researchers such as Dr. Indrajith argue that traditional bee honey collecting methods would hinder the sustainability of honeybee populations as collectors would crush honeycombs to extract all honey. This would pose a threat to larvae and young stages of growth inside the honeycomb that could ideally develop into the next colony of honeybees.

From a state level, the primary measure for the conservation of honeybees is the Pollinator Conservation Action Plan (PCAP) which was put forward by the Ministry of the Environment in 2012. However, this conservation policy is not specific to bees and takes into consideration all insects which are categorised as pollinators. But, there is no legal protection for the honeybee.

“All Lepidoptera including butterflies and moths are protected under the Flora and Fauna Protection Ordinance, but not honeybees or wild bees,” said Senior Environmental Lawyer Dr. Jagath Gunawardena. “But it is important to protect honeybees and wild bees because they are key pollinators in any ecosystem. Providing legal protection for honeybees will also put a halt on wild harvesting of bee honey which has a negative impact on their survival.” He further said that the Pollinator Conservation Action Plan never saw light of day.

In this backdrop, bee researchers are pushing for improved beekeeping education while encouraging domestic bee honey production. The breeding of resistant bee strains that are more adaptable for climate change has been discussed.

Dr. Indrajith further noted that without depending on wild colonies, methods to multiply by artificially rearing the queen bee could be developed. “Some bees are productive and some are lethargic. After finding a good strain of bees we can multiply them in the lab,” he said while adding that shelters could be provided for solitary bees that don’t join colonies.

Initiatives to introduce apitourism – an extension of ecotourism, are being discussed to make sustainable beekeeping popular among Sri Lanka’s ecotourism niche.

Today, adivasi tribes must bear a heavy cost when entering the jungles to collect bee honey unlike in the past. It would cost anything between Rs. 10,000-15,000 for a group of 5-6 individuals to go into the thick jungles in search of bee hives and honeycombs. Unlike in the past, adivasi tribes are unable to hunt and a huge expense is borne on food. They stay in the jungles for 5-6 days or sometimes even longer to obtain a good yield. “On most days we come back empty-handed. During the season we can collect around 50-60 bottles. But we are unable to even cover the production cost. The market price fluctuates because people who engage in domestic bee honey production have started selling bee honey at nominal rates. So, we can’t charge a premium price. It’s a premium product because we sacrifice our blood and sweat to provide authentic bee honey to people. Many of us are indebted. Some of us have even obtained bank loans. Back in the day we weren’t indebted to anyone when collecting bee honey because it’s part of our tradition. But things have changed,” Suda Wannila Aththo said, adding that perhaps in time to come their community too would have to adjust to modern methods of bee honey production as it has now become a costly process.

This story was produced under the CIR- CANSA Media Fellowship Programme. The It was originally published in Daily Mirror on 19 February 2025.