The island nation’s north saw the last phase of a brutal civil war. As war widows and mothers of the disappeared reclaim their land from the conflict, they seek to turn another disaster into a story of resilience.

Rukshana Rizwie, Editor: Pallavi Pundir | 1 May, 2025

Santhirasegaram Sivaranjini kneels in the dry soil of her home garden, her hands caked in dirt as she carefully plants seedlings. The sun beats down relentlessly, a reminder of the prolonged drought that has ravaged her land. Around her, the remnants of last year’s failed harvest — withered stalks and cracked earth — tell a story of loss. But Sivaranjini is determined. “This year, I will try again,” she says, her voice steady despite the weight of her struggles.

For the 44-year-old war widow and a mother of three, this small plot of land is more than a garden. It’s a lifeline. She endures the dual devastations of Sri Lanka’s recently concluded 26-year-long civil war and the escalating impacts of climate change.

Sri Lanka’s civil war was a conflict between the Sri Lankan security forces and a separatist group of Tamil minority called the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). In the final stages of the conflict in 2009, the Sri Lankan military ruthlessly bombed LTTE strongholds in the north. The death toll – mostly civilians – is estimated to be up to 100,000. One of the victims was Sivaranjini’s husband, who died from injuries sustained during the shelling of Oddusuddan, a township that witnessed some of the fiercest fighting between the Sri Lankan forces and the LTTE.

Today, the war is over, but not for Sivaranjini.

“This year has been the most devastating,” she tells Asian Dispatch, her voice tinged with exhaustion. “There was no rain during the weeding period, and then too much rain just before harvest. Severe droughts in between. Everything was destroyed.”

Sivaranjini is the sole provider for her home, and her story is not unique. In northern Sri Lanka, particularly in Mullaitivu, Tamil women — many of whom are war widows or survivors of the conflict — are facing the compounded impacts of prolonged droughts and erratic weather patterns.

One of the significant impacts that the conflict has had is the increased number of female-headed households (FHH) in the Northern Province including Mullaitivu district. Out of the 5.2 million households in Sri Lanka, an estimated 1.1 million households or 23 percent of the households are FHH.41. Of that it is estimated that women head 58,121 households in the Northern Province.

For over two decades, the north has experienced drastic climate shifts, with severe droughts rendering vast tracts of agricultural land infertile and torrential rains causing floods. Climate change has robbed these women of their primary livelihood—farming—and forced them to seek solutions for survival.

A time-lapse of Oddusuddan, in Mullaitivu district, highlights how much the landscape changed from 1966 onwards. The landscape shows lush greenery in the late 90s to parched and infertile lands in the 2000s. Video: Rukshana Rizwie; satellite images via Google Earth

Sivaranjini’s family once thrived on farming. Before the war, they earned at least LKR 1,000 (roughly $3) per day, growing black gram, green gram, maize, ground nut, cowpea, sesame, kurakkan, red onion, big onion and soya beans.

But the conflict and its aftermath left deep scars. Her eldest son, who sustained severe fractures during the shelling, requires frequent hospital visits. With no borewells to irrigate her three acres of land, Sivaranjini relies on borrowed water from a nearby well—a precarious arrangement. “If the other landowners see my plants bearing fruit, they won’t let me fetch water,” she says. This makes her increasingly reliant on the rain cycle.

Mullaitivu is located in Sri Lanka’s dry zone, and has long been a hub for growing red rice and other field crops such as groundnut, green gram, black gram and pulses. This is also where the last phases of the civil war were fought.

Over the past few decades, the district has experienced significant shifts in its rainfall patterns, disrupting traditional farming practices and challenging the resilience of its agricultural dependents. Data from 1961 to 2002 reveals a complex picture of climate change impacts, with Mullaitivu standing out as one of the few regions in Sri Lanka where annual rainfall has increased, even as the number of rainy days has declined.

According to academicians Sulakshika Senalankadhikara and L Manawadu, who both teach at the Department of Geography at the University of Colombo, who are co-authors of a study, Mullaitivu recorded an increase in total annual rainfall of 7.215 mm per year over the 42-year period from 1961 to 2002. However, this increase in total rainfall has not been accompanied by a rise in the number of rainy days.

“Mullaitivu experienced a decline in the number of rainy days by 0.818 days per year. This suggests that while the total volume of rainfall has grown, it is now concentrated in fewer, more intense downpours,” Senalankadhikara says, adding that this shift has significant implications for agriculture, as it leads to longer dry spells interspersed with heavy rainfall events that can cause flooding and soil erosion.

For example, the study’s spatial interpolation maps show that Mullaitivu’s rainfall patterns have shifted significantly over the decades. While the district once received relatively consistent rainfall, it now experiences more extreme fluctuations, with periods of intense rainfall followed by prolonged dry spells. This variability is particularly challenging for paddy cultivation, which relies on consistent water availability.

Spatial interpolation maps of Sri Lanka show that rainfall patterns have changed over the years with the district now receiving torrential pours.

According to V Pathmanandakumar of the Department of Geography at Eastern University in Sri Lanka, the land cover in Oddusuddan has undergone significant changes over the past two decades. His research, which produced thematic maps illustrating land-use changes between 1997 and 2016, reveals a troubling trend: A 5.88 square kilometre decline in vegetation cover.

“In 1997, about 453.02 square kilometres of the Oddusuddan division was covered with vegetation,” Pathmanandakumar explains. “By 2016, that figure had dropped to 447.14 square kilometres.”

Legacy of loss in the north

In the north, the story of the climate crisis is closely intertwined with the legacy of loss among the Tamils. Sri Lanka is a Sinhalese Buddhist-majority country, and Tamils form its largest minority, making up 12 percent out of its 23 million population. The community has historically faced systemic discrimination since the country gained independence from British colonisation in 1948. Sinhalese Buddhists have great influence in Sri Lanka’s institutions, including politics, judiciary and police, leading to further marginalisation. Ethnic fissures, compounded by violence and discrimination, eventually erupted into a civil war in 1983, which lasted until 2009. The war is over now, but not for 3.1 million Tamils, who still reel from the impacts of war. Women and children are disproportionately impacted by its outcomes.

Sasikumar Ranjinidevi, who lives 30 km away from Sivaranjini, says the war has left her feeling like a stranger in her own land. Her husband and family members surrendered to Sri Lankan security forces during the final years of the armed conflict. Her kin are now among an estimated hundred thousands of disappeared, with no sign of their return. This left Ranjinidevi to shoulder the burden of raising her children and rebuild their shattered lives alone.

According to the United Nations Human Rights Council Report, Sri Lanka has the second highest number of enforced disappearances worldwide, tipping 100,000 disappearances.

“I see the sorrow etched on my son’s face,” she tells Asian Dispatch. “There are days he returns from school in a solemn mood, refusing meals and weeping alone for hours or even days. He misses his father terribly.”

The weight of her loss is palpable. Yet, Ranjinidevi masks her grief, knowing life must go on. After the end of the armed conflict, she returned to her hometown to reclaim her land and rebuild what was lost. “Our harvests and planting cycles always revolved around the weather,” she recalls. “It was like clockwork. Now, it’s as unpredictable as our lives. Over the years, we’ve abandoned our land, plot by plot. Today, an entire acre lies barren and unusable.”

Ranjinidevi’s lands are vast but her farms are small, she can only grow what the weather allows. Today she is tending to wheat and hopes her vegetables will withstand the next downpour. Photo: Rukshana Rizwie

What little remains of her land tells a story of struggle. Ranjinidevi once grew vegetables in her home garden and pulses in the fields. “Either the seeds drown in excessive rainwater or the crops are washed away before we can harvest them,” she explains. Though the rains are brief, they are devastatingly intense, leaving no chance for recovery.

Knee-deep in debt, Ranjinidevi has borrowed from both private and government banks. “We can’t make enough. Nothing grows, and when it does, it’s destroyed. Whatever I hoped to salvage has been lost. I can’t even pay the interest on my loans. I don’t know what to do, and there’s no one to share my worries with,” she says.

During droughts, the situation worsens. Wells dry up, forcing them to buy drinking water. “The brinjals and pulses I planted withered under the scorching heat and lack of water,” she says with despair. ”There was a time when lorries would come to our lands to load up on onions to take to [capital city] Colombo,” she said. “Today we jump for joy at the sight of a growing single onion.” The dry spells are the hardest to bear, she says. The severe drought in 2018 she and her family experienced, lasted for more than eleven months and affected the western part of the entire district.

She says no matter how much effort or money she invests, the force of climate change is against her. “It isn’t supposed to rain this month (February), but it has been pouring and last year around this time, we experienced floods.”

When is the next big drought?

Based on the research by a group of scientists from Malaysia-based Universiti Sains Malaysia, the next significant drought in Mullaitivu is likely to occur during the southwest monsoon season, which spans June, July and August. Historically, these months have been identified as the driest in the region, with minimal or no rainfall recorded in some years. The study highlights that drought conditions often originate in the western part of the district in March and progressively spread eastward, intensifying during the peak dry months of July and August. This pattern is influenced by geographical factors and the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), which has a strong correlation with drought occurrences in the area.

Given the cyclical nature of droughts in Mullaitivu, the southwest monsoon season of 2025 is expected to follow this established trend. The combination of high temperatures, increased evaporation rates, and reduced rainfall during these months will likely exacerbate water scarcity, impacting agriculture and daily life.

The study also notes that the IOD plays a significant role in shaping these conditions, with positive IOD phases linked to warmer sea surface temperatures and reduced rainfall in the region.

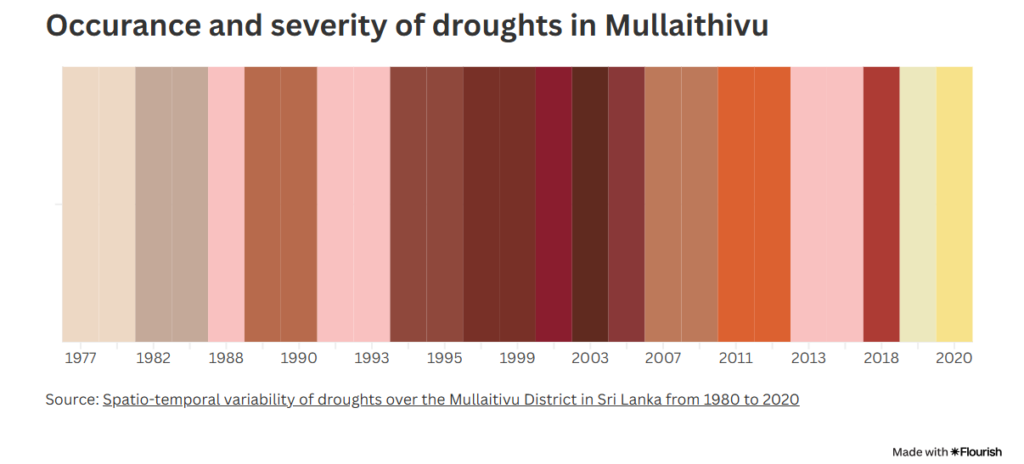

A heatmap based on scientific studies conducted in Mullaitivu which shows the occurrences and incidents of severe droughts from 1977 onwards to date. Graphic: Rukshana Rizwie

A struggle for identity and land

To understand the climate crisis for Sri Lanka’s north, one needs to acknowledge the historical role land plays in Tamil identity. The community is believed to have descended from the Jaffna kingdom and are natives to the country. Despite the legacy, the Sri Lankan government listed them as a separate ethnic group and even removed the Tamil language as an official language in 1956 – which was later reinstated in 1987. The Sri Lankan government is also accused of erasing Tamil legacy by destroying archeological evidence of the community’s historical roots. With the Tamil culture, language and history under siege, the LTTE was borne out of the idea of a Tamil “homeland” where LTTE founder V Prabhakaran famously said that the Tamil race is “deeply rooted” to the northern soil. After the war, the Sri Lankan government has been waging a quiet war on Tamil land. Most of it is on agricultural land.

Sasikumar Santhidevi was eight months pregnant when her husband died during the shelling in the war. She fled to save her and her unborn baby’s lives but when she came back in 2011, her land was occupied by the Sri Lankan military. Military occupation of Tamil land became a jarring reality for thousands of civilians like Santhidevi, who returned after the war only to find camps, bases and High Security Zones on their agrarian and familial land. According to the Adayaalam Centre for Policy Research, an advocacy group, the military held 30,000 acres of land in Mullaitivu in 2019, a decade after the war.

For Santhidevi, the military eventually let go of some land but a portion of it is still occupied by Sri Lanka’s Department of Forests.

“[When I came back after the war],I couldn’t locate my home, Santhidevi recalls. “The entire area was a jungle. My mother and my little children took axes and began to cut through the dense shrubbery. I remember one occasion when we were having a meal during a brief respite, the army commander of the area came over and told us to leave everything and go.”

Santhidevi didn’t give up: “We lived on this land and had all the documentation to prove it, so I went to court. The army offered us money in exchange for an acre of land, but we refused. We wanted to keep our land.” Once she was finished dealing with the army, she confronted another issue: The Department of Forests, which still claimed an acre of her land. “We can’t access it to date,” she says, leading us to a spot marked with concrete poles. “They’ve fenced the land, and if we are to go to court over it, we need at least LKR 100,000 ($334) in legal fees, money which we don’t have.”

Despite the Department of Forests’ claim on the land, Santhidevi says she sees them planting and harvesting pulses each year, which they later sell.

Santhidevi shows us the concrete polls that separate her own lands from the rest of the plot. Photo: Rukshana Rizwie

Asian Dispatch investigated the land occupation in Mullaitivu district.

In response to a Right to Information (RTI) petition submitted by us, the Mullaitivu secretariat responded with a calculation that showed a total of 4,859 acres that still remain occupied. Only 2,891.75 acres have been released so far. Of the five divisions in the Mullaitivu, Karaithuraipatru (Maritimepattu) is the most heavily occupied. Over 4,000 acres of the total occupied land fell within this division.

| Division | Total seized by tri-forces | Land Released (acres) | Land Remaning (acres) |

| Karaithuraipatru | 6809 | 2764 | 4045 |

| Thunukkai | 429.25 | 0.25 | 429 |

| Oddusuddan | 188 | 2 | 186 |

| Puthukudiyiruppu | 284.5 | 115.5 | 169 |

| Manthai East | 40 | 10 | 30 |

| Total | 7750.75 | 2891.75 | 4859 |

Keppapulavu is where hundreds of residents – including Santhidevi – were forced to flee their homes during the final stages of the war in 2008. Soon after, the military took control of more than 202 hectares of Tamil-owned residential land, incorporating the former residents’ homes into vast military camps. The army now uses the land for farming and maintaining guarded military camps, despite promising that they’ll return the land as part of the government’s justice, peace and reconciliation process.

The RTI petition also revealed that Sri Lanka’s Forest Department has expropriated 32,110 acres of land, while the Wildlife Department continues to lay claim to 23,515 acres. The Sri Lankan military, at the same time, continues to occupy large tracts of state and private land in Mullaitivu, estimated to be 16,910 acres, according to a research by the Oakland Institute researchers.

Although the government claims that the military has released 90 percent of occupied land in the Tamil-majority north, a Human Rights Watch report last year found that this figure was impossible to verify as there was “no publicly available accurate and comprehensive mapping of land occupation”. The Adayaalam Centre for Policy Research estimates that the military still occupies 12,140 hectares of land in Mullaitivu alone.

A Google Maps search shows several key military institutions scattered across Mullaitivu, including the Sri Lankan Air Force base and station, the Sri Lanka Army barracks, the security forces headquarters, a military barracks next to the GE Office, the 6th Battalion Sri Lanka Electrical and Mechanical Engineers base, the 9th Sri Lanka Army Signal Corps, and the Mullaitivu army base hospital.

A simple Google map search reveals just a few of the military installations and camps dotted along the main roads in Mullaitivu. Screenshot: Google Maps

At the same time, the Sri Lankan Army has commercialised the agricultural land in question, by selling the produce to landowners. The military has been running commercial projects such as resorts and shops in high-security zones, which prevents the resettlement of displaced Tamils. For example, Valikamam North in Jaffna district is approved for resettlement, but large military camps and bungalows remain on private land, and access to many areas continues to be restricted.

In 2023, the Sri Lanka army admitted that several of its battalions had been stationed on private land, occupying 70.05 acres of private land. Many of these military companies are not even pinned on a map to be easily identified or located.

Images on the Sri Lankan army website show its military personnel engaging in farming. Photos: Army.lk

Building a new life, one garden at a time

Pulasthi*, a war survivor who requested anonymity, expressed exhaustion from monitoring the Sri Lankan army’s occupation of two acres of her Keppapulavu farmland. She recounted fleeing with her husband and two children to Mullivaikkal during the war’s final phase. While taking refuge in Mullivaikkal camps, her husband and eldest son were killed by a shell that struck their camp. The army forced her to leave her home in 2009, moving her to Manik Farm. Manik Farm was a military-run displacement camp, which recorded several human rights violations. Pulasthi was there until 2012, when the site was shut down and its residents relocated to another camp in Sooripuram. Pulasthi was given a new house in another village but returning to her land in Keppapulavu isn’t allowed.

“The land I’m on isn’t mine,” she says. “It’s only 40 perches. I used to have two acres [in Keppapulavu] where we farmed and lived comfortably. This land is barren. We have no electricity, and I can’t make ends meet.”

Today, in a parched home granted to her, Pulasthi finds solace in her home garden, where she’s planted chillies and palm trees. What she lacks is irrigation as her plot of land is situated at a lower elevation, which makes it vulnerable to flooding during rainfall. “Either the water is too salty or it evaporates too quickly,” she claims. “I pray to God it rains soon.”

Pulasthi looks out at the expanse of land beyond the confines of her humble home. Photo: Rukshana Rizwie

Daily life often revolves around accessing clean water from wells and nearby tanks. Now, rising salinity levels, exacerbated by droughts and saltwater intrusion, is making this increasingly difficult. The consequences are far-reaching: Water resources are under immense strain. Major reservoirs experience fluctuating water levels, minor irrigation systems dry up rapidly, and streams flow irregularly. Just like Pulasthi described, the groundwater sources are depleting, and water quality is declining due to high salinity.

Compounding these physical vulnerabilities is the district’s low socioeconomic resilience. With a disaster resilience index of less than 30 percent, Mullaitivu residents struggle to cope with and recover from climate shocks. Poverty, limited income diversity, low financial inclusion, and inadequate social protection systems leave communities ill-equipped to face long-term challenges. The result is a cycle of hardship that undermines well-being and hampers recovery efforts.

“We live because dying isn’t a choice,” she says, her voice steady but her eyes betraying the weight of her struggles. “What can I do? I’m cornered in this piece of land that isn’t mine. We grow and eat whatever we can and live for the sake of our children.”

Sivarasa Rajeshwari, a war widow with four children, says that agricultural resilience is the only hope for Tamil women. The 46 year old had fled the war to Puthukudiyiruppu, a small town in Mullaitivu, and was displaced several times without money or belongings until she came back home to reclaim her land – and sustenance. “Growing vegetables not only feeds my family but also brings in a little extra when I sell them at the market,” she says. In 2018, the worst drought in memory wiped out her entire harvest. “I’m grateful it was only that year,” she says, her relief tempered by fear. “I pray we never see a repeat of it.”

Despite the erratic climate, Rajeshwari says it’s necessary for women like them to adapt. “Only certain vegetables can survive these conditions,” she explains, gesturing to a field of eggplants. “Thankfully, I have a well with a motor to pump water to the plants. Before, we carried water in buckets for each plant —it was exhausting.”

Rajeshwari inspects her eggplants to ensure the leaves are not infected with pests. She tells us that she has a few more weeks before she can harvest them. Photo: Rukshana Rizwie

Despite the hardships, the resolve of the women in Mullaitivu remains unshaken. For Sivaranjini, the path forward is clear.

“I will keep working,” she says, her hands returning to the soil. “This land is all I have.” Her words echo the quiet determination of a community that refuses to be defeated, even as the odds stack higher against them.

In the face of war and climate change, women’s resilience is a powerful reminder of the human capacity to endure and adapt. Amid the rubble of loss and the scars of conflict, new life sprouts in the women’s home gardens, a testament to hope and perseverance.

This story was supported by a grant under the Open Climate Reporting Initiative by The Centre for Investigative Journalism, administered by DataLEADS and originally published on Asiandispatch.